| ABOUT | MISSION |

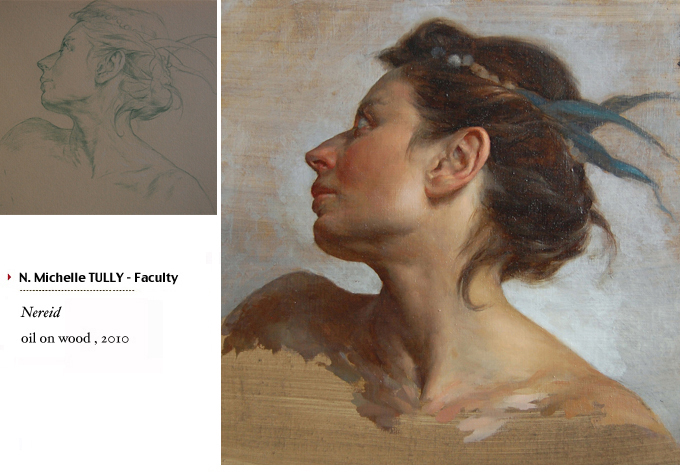

“Execution is the mother of painting, discourse is its father.”

– Charles Dufresnoy, Observations sur la peinture 1649

[Le discours est le père, l’execution la mère de la peinture.]

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

“The Next Eclectics”

Only light feels like light, and only nature reveals the form of nature.

Studio Escalier has a simple mission, and a traditional one. It is dedicated to drawing and painting, to the development of enlightened creative vision, and to the expression and definition of humanity through pictorial form.

What this means — after the competing idealisms and polarisations of Modernism (1790-1970), after the pastiche, aesthetic severity, nostalgia and pluralism of the Pop, Minimalist and Postmodern periods — is that the founders of this school seek to define a new sort of vital eclecticism in art training, eclectic in the spirit of the first true art academies of 16th century Italy.

As the Carracci family did before us, we draw upon the recognized, brilliant artistic achievements of our professional grandfathers as the basis for a new visual study of nature, a new definition of the classical ethos, and a new proposition of what is beautiful, natural and essential to the study, art and practice of painting.

The Carracci, who were the first “school of the eclectics”, were the direct heirs to and pulled equally upon four schools of thought, represented by Michelangelo, Raphael, Correggio and Titian. (Florence, Rome, Parma and Venice). They revived the studious, naturalist, classically imaginative spirit of the Renaissance, re-grounded and deepened the lust for life and intellectual territory of their forebears, and built the foundation of both the Baroque academies and the art of the Enlightenment.

But we do not propose that the Carracci family or their past world actually holds any answers for us. We are probably only like them in our belief that we should propose a better line of questioning to art students, and find a better way of generating new questions, and not hand out a series of unreasoned answers, dogmatic systems or sure-fire methods.

We differentiate between instructing people how to make a politically acceptable, historically conventional or commercially stylish product and teaching them to see, recognize, and question their work artistically. We seek to apply all the criticality and intellectuality of our own era to a classical artistic question: in what way shall we hold a mirror up to nature? And, perhaps even more, how shall anyone learn to do so?

Our eclecticism is not equivalent to pluralism, which proposes everything is beautiful in its own way. Our eclecticism is not an “art movement” at all, per se, but rather a recurring sensual and intellectual persuasion among the strongest schools of painting since the Renaissance. Eclecticism in painting derives the strongest creative principles from a close visual study of nature, and imposes these principles upon its artists, making strong formal judgments and selections about what makes something aesthetically alive and why.

We have a rich and storied history, yet our eclecticism is not equivalent to historicism, either. We do not seek to squeeze our perceptions into past academic norms, nor do we wish to base our education upon preconceived systems, received knowledge, prior assumptions or the conclusions of any other painters. We seek instead to discover what nature is really capable of showing us, through constant visual comparison to the live figure, the constant critical search for natural organizing principles, and the application of pictorial intellect. When our own minds are the mirror before nature, our own paintings can transform into a teacher, into a foundation for all excellence.

Our school of thought is not based on telling people how to put things together “the way we do it”. Rather it is a way of taking apart what a student already does and challenging it at the level of its creative principles and fundamental perceptions. We uphold a standard, which is a far different thing than applying rules. We seek to refertilize our minds and refound our art upon a naturally stronger, more clearly perceived, vitally self-organized base. We are not technicians, copyists or imitators. We are conscious and conscientious formalists.

Eclecticism is also another word for the artistic dialogue that decides what is a most vital addition to our previously accepted painting culture, and what is not. It has historically sought to define what is most natural and urgent in art education and what is not. It is synonymous with the healthy self-critical intellect of the Euro-American academic tradition (1589 – present), the kind of creative intelligence and evaluation that gave birth to both Neo-Classicism and Modernism in the first place (to say nothing of the Classicism, Mannerism, Caravaggism, Poussinism, or Rubenism that came before them.)

The faculty of our school are the direct heirs to and pull equally upon four Modern schools of art, two French and two American ones:

| the Academie Julian | (Rococo Revivalism/Belle Epoque/Art Nouveau painting) |

| the School of Paris | (Cubisme/Fauvisme/Intimisme) |

| the Golden Age of American Illustration | (Brandywine/Grand Central School/Art Students League) |

| the Cape Cod School | (American Impressionism/Hawthorne/Hensche) |

I am tempted to say our teaching pulls upon the understanding of Jules Lefebvre & J.J. Benjamin-Constant, of Matisse & Vuillard, of Loomis & Cornwell, of Hensche & Dickinson, more or less in equal measure, but that we retain our own arsenals of meaning.

It is even more accurate to say that none of our faculty emerged apart from an established, strongly eclectic master, yet each of us is an unrepeatable, unique evolution of the tradition. I paraphrase my master by repeating that it is standard for strong painters to develop inside the studio of a strong painter, inside his structural ideas and his perceptual guidance, but:

the strongest artists will overcome that influence only by deliberately subjecting and subordinating their own work to what can be called the governing, critical, decisive principles of life. We still call these ideas “Nature”.

Let me add: it was always communicated to me that the strongest art does NOT come from the urge to “do my work”, “do or make something pretty”, “produce paintings” or “reproduce what I see”, but only from the presiding urges to explore, to question, to learn and, thereby, to consciously & visually relate both vital & natural principles. This is the intellectual, emotional and spiritual underpinning of grand pictorial thought.

In this way, the most insightful and powerfully principled art instruction seems to have, in the longest view, an essential, inevitable, but only limited effect upon the strongest art. Art grows and evolves by practice, and is as destined for growth as the principles which underlie its design will allow.

It might be necessary to be dogmatic on this point: some principles are more pictorially fertile, insightful, paradoxical, beautiful, abreactive, complex, energizing and naturally powerful than others, are truly more alive than others, and our best practice as artists and teachers of art is to draw upon these principles with a conscious prejudice.

In conversation with such principles, we find our actual selves. We do not seek to construct a historicized consciousness, but to grow and reveal a singularly historic one. That is the very identity of art.

We are certainly not the last eclectics, and not the last natural classicists. We are only some of the stronger ones, and some of the next. We are beginners, all over again, but we do not arrive empty-handed.

As in 1589, the vital cultural forces of our grandfather schools are now spent, but they each contribute directly to the character, creative basis, sensibility and growing direction of our school of thought, towards an utterly new kind of vivid, refined, natural, humane, beautiful, contemporary classical art. It is an idea that is open to definition.

Timothy STOTZ

12 September 2003

Argenton-Chateau, France